A new dog eats the man who fed it, should it be punished?

A justice will heal the beast's rotten soul, shouldn't Hamlet help?

The world is changing, could Hamlet understand it all without taking action?

Hamlet's character willing, he chooses to find “direction through indirections”

“Who is there?”

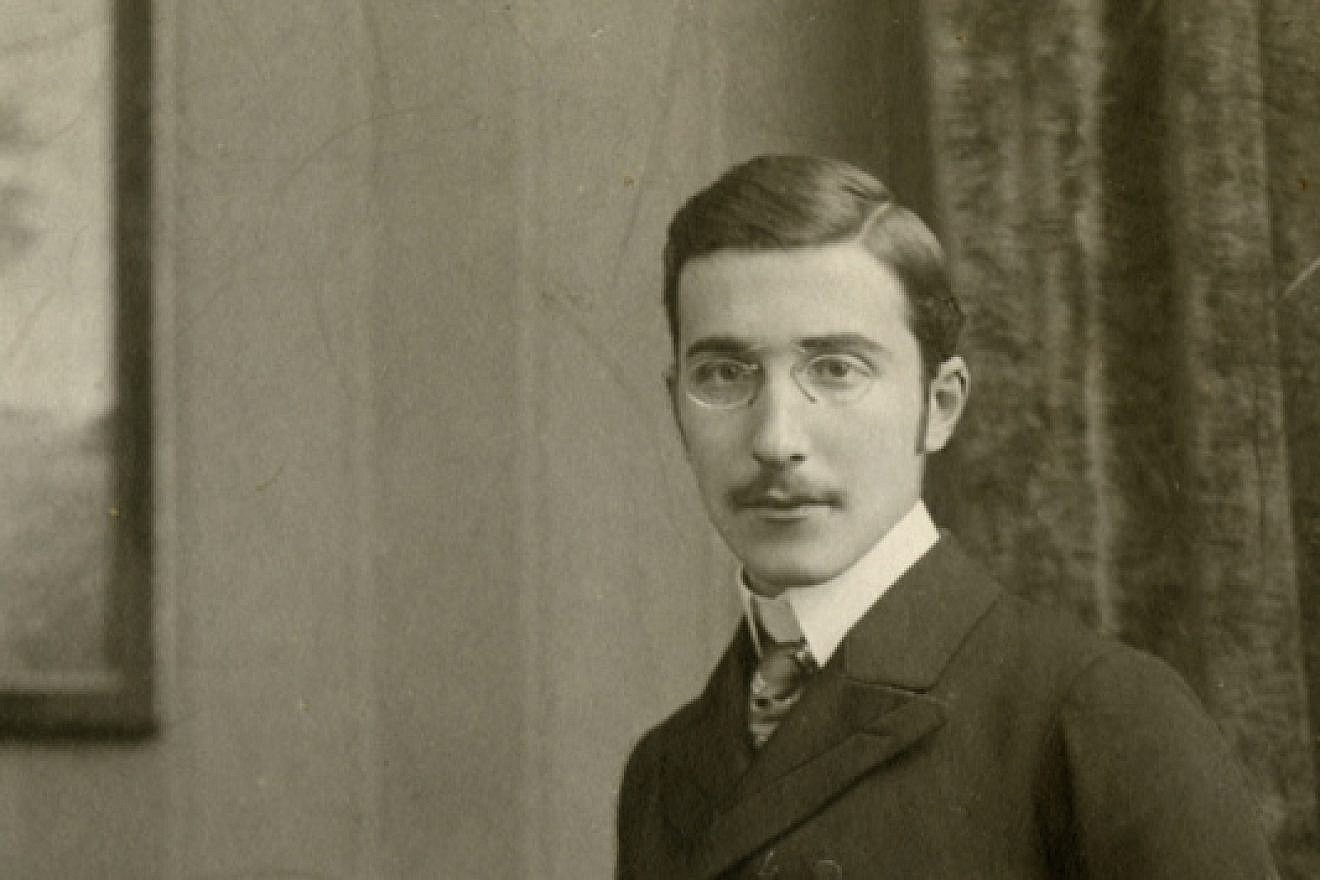

In William Shakespeare’s Hamlet Act II, Denmark's “most immediate to the throne,” Prince Hamlet* is not his former self under the watchful eyes of the court (II.2.51, II.2.58). Hamlet explains his change to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, friends from university, “I have of late, but wherefore I know not, lost all my mirth, forgone all custom of exercises, and indeed, it goes so heavily with my disposition that this goodly frame, the Earth, seems to me a sterile promontory.” (II.2.318) He could be saying these words premeditatedly (I.5.187, II.2.402, II.2.386) to deceive the court. Recently, he had to reconcile with his mother Gertrude’s hasty marriage to his uncle Claudius, now King, (I.2.161) unfortunately a month after his father’s funeral. He also experienced an unnatural event of conversing with a ghost that asked him to take revenge, claiming it was his father’s soul and his father was murdered by his uncle (I.5.29). Hamlet is in the process of finding out the truth and figuring out what his true will is.

As a result, the court finds Hamlet distempered, lunatic, and mad. For example, Ophelia, Hamlet’s lover, finds him in her closet, “with his doublet all unbraced, No hat upon his head, his stockings fouled, Ungartered, and down-gyvèd to his ankle, Pale as his shirt, his knees knocking each other, And with a look so piteous in purport” (II.1.87). It is true that he walked into her private closet, and it could have been due to a madness for her “love,” but it is not a shape any prince of Denmark would usually portray, especially “The glass of fashion and the mold of form, Th’ observed of all observers” (III.1.167) as Ophelia used to know Hamlet.

“Get thee to a nunnery”

Not only is Hamlet personally frustrated with his inaction about the request of the ghost to avenge his father’s murder, but he also finds himself not delighted with the people in Denmark (II.2.386). Everything around him seems “Most foul, strange, and unnatural” because of his mother’s marriage to his uncle, and change of people’s attitude once his uncle became king. In other words, the world is not working the way he thought it did, and especially, the people are not showing moral character or virtue. This lack of delight in people explains his treatment of Ophelia and Polonius, a counselor to the King and Ophelia’s father. Therefore, he claims Denmark is the worst prison with “many confines, wards, and dungeons” (II.2.265).

But we also see that he didn’t lose his pride and his best (V.2.224, II.2.593). Hamlet wrote his heartfelt wish to Ophelia; he said, “Doubt thou the stars are fire, Doubt that the sun doth move, Doubt truth to be a liar, But never doubt I love” (II.2.124). That love might have been towards her, but the mere fact that he really loves implies that he is a believer of some sort of ideal truth. In other words, he doubts everything, but he doesn’t doubt he loves. Through that love, he wants to see life as what it is and lead a life for something worthy and in a serious manner, like a priest (I.5.187) seeking to understand the God, or a Socratic scholar questioning his will**, or a scientific statistician modifying the likelihood of the truth after a new piece of information becomes available (I.2.23).

“Mark me!”

One of the things Hamlet loves is theater. For example, when Hamlet shared with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern that he had lost all his mirth, that life seemed empty, and that men no longer delighted him (II.2.318), they knew that Hamlet would enjoy the players coming to Elsinore by smiling at Hamlet’s melancholic speech. Moreover, his respect and reverence for the theater can be seen when Hamlet defines theater as “the abstract and brief chronicles of the time” (II.2.549) and encourages Polonius to treat the traveling players with honor and dignity (II.2.555). Furthermore, Hamlet might have performed in a play at the university, as his acting skills shine in his recital of Aeneas’ tale about Priam’s slaughter. Not only did he know a part of the play by heart, but he was also able to give advice and coach the players.

“Adieu, adieu, adieu. Remember me”

To enjoy the theater, Hamlet asks the players to perform the Murder of Gonzago, and he requests them “for a need, study a speech of some dozen or sixteen lines, which [Hamlet] would set down and insert in ’t.” What was the need? I argue that Hamlet hoped to grasp the ultimate guiding principles in the chaos he finds himself in. Once the players came to the Elsinore, he found an even better way to observe human life, including his by “adding some dozen or sixteen” lines to the Murder of Gonzago, the play he requested. By adding lines, Hamlet wanted to make it even more similar to his own struggle in his mind to let theater do what it does—to reflect nature, and especially the nature from his perspective—to understand himself, and possibly to remember (I.5.89). Hamlet’s advice for theater players was that the best theater should “Suit the action to the word, the word to the action, with this special observance, that you o’erstep not the modesty of nature” (III.3.18). This philosophy of theater supports the argument above that he wanted the players to resolve his own struggle to understand what is going on within and outside of him, and to allow himself to see as the observer as his understanding of the world is changing. If the theater did its best depicting nature from his perspective, he might have understood it fully picking up on something he might have missed.

The Murder of Gonzago must have been very similar to Hamlet’s own experience. The request to play modified version of The Murder of Gonzago came right after Hamlet’s and the First Player’s recital of Aeneas’ Tale about Priam’s slaughter, which depicts old Priam being slaughtered by Pyrrhus, and Priam’s wife, Hecuba, showing devotion to him after his death. The speech that Hamlet recited right away shows that the play was in his mind as he struggled with what to do about the ghost’s request. From this, we might formulate the theme of the Murder of Gonzago. Priam’s slaughter is quite similar to the story that the Ghost depicted, except that old Hamlet was poisoned in his ear during his nap time and Gertrude married Claudius. The Murder of Gonzago might have also depicted a similar story of a righteous king in his old age getting killed by an unworthy person who claimed his fortunes (III.4.63) even though the play doesn’t fully disclose what the play might have entailed; therefore, The Murder of Gonzago could have depicted the nature and experience that Hamlet was going through in his head.

“Do it, England”

Ultimately, Hamlet decides to trap Claudius with a play that reflects the story of his father’s murder to acquire a data point that would be crucial for making a decision. Remembering was not enough for Hamlet. The First Player’s recital of the slaughter of Priam, and how the player was moved by Hecuba’s devotion to her husband Priam and her loss of everything, shook him to realize that he has a duty to take action not just understand—to show character, not just share what he found as existence and observe what he already knew. He didn’t want to continue existing as “a dull and muddy-mettled rascal, peak like John-a-dreams, unpregnant of my cause, and can say nothing” (II.2.593), which equaled being self-absorbed and having no courage to act. In order to say something, he needed more information about Claudius’s true form and decided to trap Claudius with his play The Mousetrap, the play-within-play, to trap his confession with the help of the players (II.2.617), changing his focus from understanding his experience to seeking more information important for taking the right action (II.2.630).

Textual Evidence

1. (II.2.51) “the very cause of the Hamlet’s lunacy”

2. (II.2.58) “distemper”

3. (I.5.187) “As I perchance hereafter shall think meet To put an antic disposition in That you, at such times seeing me, never shall With arms encumbered thus, or this headshake, Or by pronouncing of some doubtful phrase.”

4. (II.2.402) “I am but mad north-north-west. When the wind is southerly, I know a hawk from a handsaw.“

5. (II.2.386). “Gentlemen, you are welcome to Elsinore. Your hands, come then. Th’ appurtenance of welcome is fashion and ceremony. … You are welcome. But my uncle-father and aunt-mother are deceived”

6. (I.2.161)“She married. O, most wicked speed, to post With such dexterity to incestuous sheets! It is not, nor it cannot come to good.”

7. (I.5.29) “If thou didst ever thy dear father love-, Revenge his foul and most unnatural murder”

8. (II.2.386) “it is very strange: for my uncle is King of Denmark, and those that would make mouths at him while my father lived give twenty, forty, fifty, a hundred ducats apiece for picture in little. Sblood, there is something in this more than natural, if philosophy could find it out”

9. (V.2.224) Hamlet has “been in a continual practice” of sword fighting since the first act

10. (II.2.593) “I will have these players Play something like the murder of my father Before mine Uncle…The play’s the thing Wherein I’ll catch the conscience of the King”

11. (I.5.187) “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio Than are dreamt of in your philosophy”

12. (I.2.123) “I pray thee, stay with us. Go not to Wittenberg.”

13. (II.2.318) “this most excellent canopy, the air, look you, this brave o’er hanging firmament, this majestical roof, fretted with golden fire-why, it appeared nothing to me but a foul and pertinent congregation of vapors.…. Man delights not me, <no,> nor women neither.”

14. (II.2.555) “Use every man after his desert and who shall ‘scape whipping? Use them after your honor and dignity.”

15. (III.4.63) “Look here upon this picture and on this, The counterfeit presentment of two brothers See what grace seated on this brow…. This was your husband. Look you now what follows. Here is your husband, like a mildewed ear Blasting his wholesome brother. Have you eyes?

16. (II.2.617) “guilty creatures sitting at a play Been struck so to the soul that presently They have proclaimed their malefactions.”

17. (I.5.89) Adieu, adieu, adieu. Remember me. The play-within-play helps with remembering Ghost’s words: “Let not the royal bed of Denmark be A couch for luxury and damned incest” and to take earthly revenge for his uncle and heavenly revenge for his mother.

18. (II.2.630) He doubts the ghost because the hell might be playing with him using “weakness” and “melancholy.”

*Shakespeare introduces Prince Hamlet as a student from Wittenberg, a city known for its university that taught Renaissance humanism and was the world center of the Protestant Reformation. Prior to his return, Hamlet led the life of the first modern man, immersed in a world where multiple systems of thought clash: Catholicism, Protestantism, classical philosophy, Viking shamanism. During this time, Hamlet’s worldview was also influenced by the recently enabled international travels, technological advancements, and the rise of the bourgeoisie. Within this multicultural “globe,” Hamlet constantly modified his understanding of the world as new information became available, pursuing his true will rather than merely acting on whim.

** The change of Hamlet's idea to stage modified the Murder of Gonzago, transforming it into "The Mousetrap" is an example of a Socratic process to understand his true will. After his encounter with the ghost, Hamlet went melancholic and could not take action, choosing to observe rather than act. Possibly he thought about Socrates' argument that it is better to be a victim than to commit evil without truly understanding one's will. This aligns with Socrates' question in Gorgias, "But does he do what he wills if he does what is evil?" Hamlet's inaction shows Socrates' teaching to clarify one's true will to avoid doing evil due to the perceived/apparent good. As Socrates states, "if the act is not conducive to our good we do not will it; for we will, as you say, that which is our good, but that which is neither good nor evil, or simply evil, we do not will." This philosophical teaching from Wittinberg explains Hamlet's inaction, but as an ethical struggle to align his actions with his true will in a morally ambiguous and multicultural world, where the soul of the wrongdoer might rot without justice, which Socrates preferred, while the pursuit of justice itself might lead to evil because we don’t have the full information.