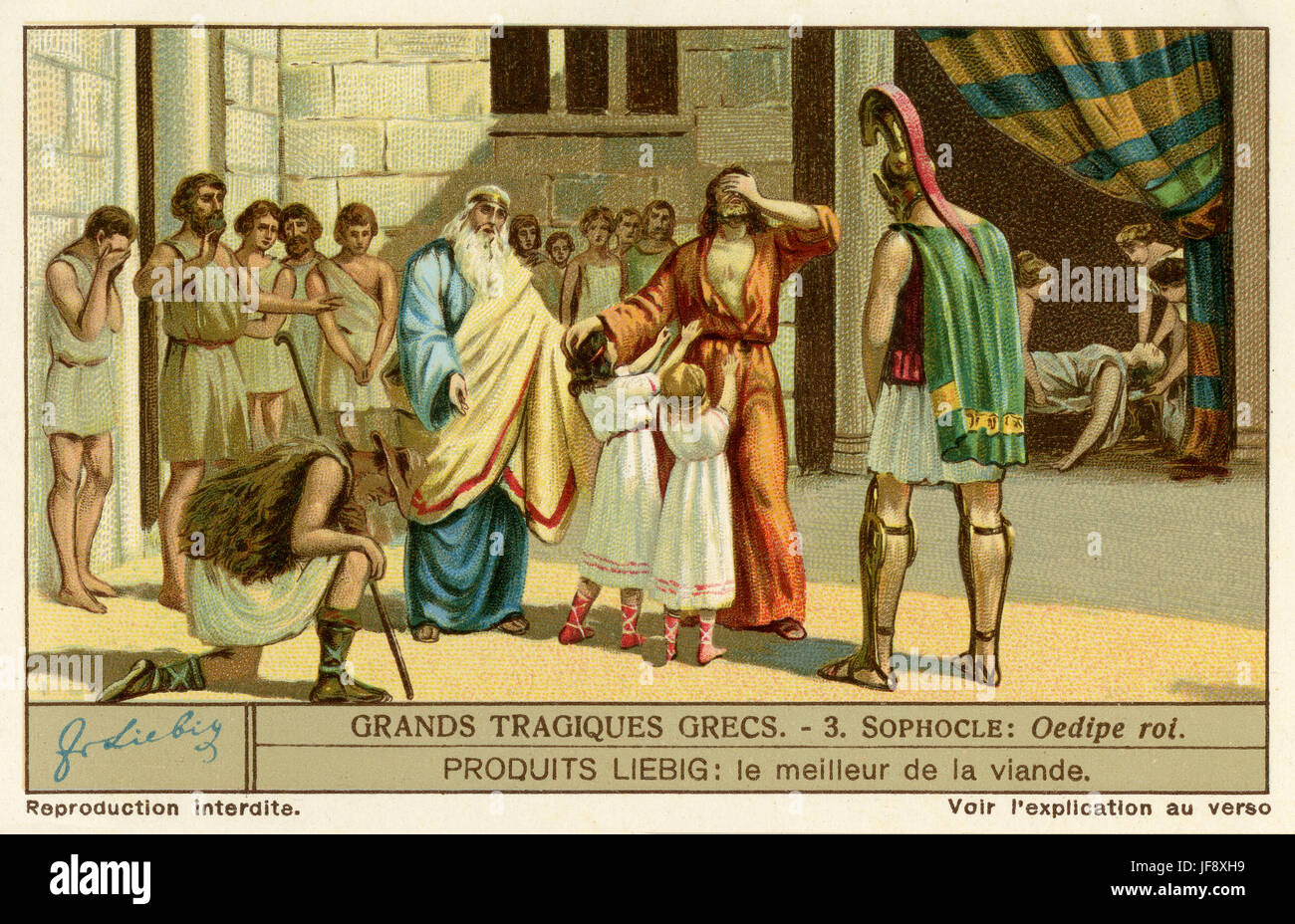

Sophocles’ King Oedipus shook me. It made me question free will, the age of innocence, and the old way of assigning blame without fully understanding others. What struck me most was how the characters in King Oedipus seem so assured of their own and others’ impulses—so certain of their reasoning, their conclusions, their understanding of the world. They assume intentions with unwavering confidence, acting as though every decision is clear-cut, every motive obvious. This is radically different from the characters in Hamlet, who are paralyzed by introspection, self-doubt, and hesitation.

It is a stark contrast in worldview—one where the past is an immutable script, fate an inescapable force, and human action merely an unfolding of an already written story. The modern mind, like Hamlet’s, is burdened by the weight of possibilities, while Oedipus and those around him act with an unflinching belief in the certainty of things.

The World of King Oedipus: A Place of Certainty

From the very beginning of the play, Oedipus does not hesitate. The city is plagued, and he seeks to uncover why. The priest approaches him, saying:

"Oedipus, ruler of my land, you see the age of those who sit on your altars… For the city, as you yourself see, is now sorely vexed, and can no longer lift her head from beneath the angry waves of death." (Oedipus the Tyrant, 14)

Oedipus does not waver. He immediately declares,

"Be sure that I will gladly give you all my help. I would be hard-hearted indeed if I did not pity such suppliants as these." (14)

He does not pause to reflect on the limitations of human knowledge or question his ability to solve the crisis—he acts, and he does so with certainty. His resolve is unwavering when he proclaims:

"I will start afresh, and once more make dark things plain… I will uphold this cause, as though it were that of my own father, and will leave no stone unturned in my search for the one who shed the blood." (132)

This certainty extends beyond Oedipus himself. The entire world of the play assumes that things happen for a reason, that the gods dictate fate, and that actions are explainable with black-and-white precision. When Tiresias hesitates to reveal the truth, Oedipus does not question the nature of prophecy or the limits of human knowledge—he simply assumes a conspiracy, declaring:

"You blame my anger, but do not perceive your own: no, you blame me." (330)

There is no hesitation, no second-guessing. Actions are interpreted as clear, intentions are presumed, and consequences are met with stoic acceptance once revealed.

Contrast with Hamlet: The Age of Uncertainty

Compare this to Hamlet, where almost every action is delayed by introspection. Hamlet’s defining feature is hesitation. His famous soliloquy—"To be, or not to be, that is the question"—is the complete opposite of Oedipus’s immediate action. Oedipus does not ask whether he should act; he acts. Hamlet, on the other hand, wonders if he should do anything at all.

When Oedipus is accused, he retaliates with a full-fledged accusation. When Hamlet is presented with a possible truth—that Claudius killed his father—he devises a test, a play within a play, to confirm it. Hamlet distrusts certainty. Oedipus assumes it.

Even when faced with absolute proof, Hamlet still hesitates. He catches Claudius praying and debates whether he should kill him right then and there. Oedipus, by contrast, does not hesitate for a moment when he believes Creon has betrayed him—he moves straight to threats:

"Hardly. I desire your death, not your exile." (616)

Oedipus assumes treachery. Hamlet questions whether treachery exists at all.

The Cultural Difference: A World Without Innocence

This certainty in King Oedipus is not just a personality trait—it reflects a different way of seeing the world. In ancient Greece, everything had a place, an order. Fate was clear, and so were human actions. People acted out of self-interest, and that self-interest was an accepted and expected truth. When Oedipus demands answers, no one stops to wonder if the question itself is flawed. He accuses Creon outright of treason, and Creon responds not with Hamlet-like defensiveness, but with a logical counterargument:

"Weigh this first—whether you think that anyone would choose to rule amid terrors rather than in unruffled peace, granted that he is to have the same powers." (583)

Creon is logical, not introspective. He does not say, "I wonder if I could have done something to give that impression." He simply lays out the facts: Why would I do this? It makes no sense.

Today, we live in a world of nuance. We assume good intentions. We analyze, second-guess, and hesitate before jumping to conclusions. But in the world of King Oedipus, there is no such hesitation. If someone has done something, their intent is clear. Jocasta, pleading with Oedipus, begs him:

"Unhappy men! Why have you made this crazy uproar? … Stop making all this noise about some petty thing." (649)

To her, this is not the unraveling of some great metaphysical truth—it is a pointless argument. The characters do not wrestle with their inner selves the way Hamlet does. Even when Oedipus realizes the truth, there is no reflection—only action. He blinds himself without questioning whether this is the best response. He simply declares:

"It is better to be blind. What sight is there that could give me joy?" (1367)

The Legacy of King Oedipus: A World Before Doubt

The world of King Oedipus is a world before the age of innocence. It is a world that assumes people act in self-interest, that the world has a rigid order, and that everything—fate, human motives, divine justice—is explainable with certainty. In contrast, Hamlet exists in a world of ambiguity, where humans are unpredictable, where good and evil blur, where action is never quite justified.

This might explain why King Oedipus still feels so alien to modern audiences. It operates on an assumption we no longer share—that certainty is possible. The play assumes, without question, that if a man commits a crime, he must be punished. No room for doubt, no space for subjective interpretation. Hamlet, by contrast, spends the entire play trying to justify one action, and even then, he only takes it at the last possible moment, when all other options have disappeared.

Perhaps the greatest tragedy of Oedipus is not his fate, but his certainty. The belief that he must uncover the truth, that he must act, that he must punish himself. Today, we might tell Oedipus to step back, to reflect, to seek therapy instead of punishment. But in his world, there is only one response: clarity, action, consequence.